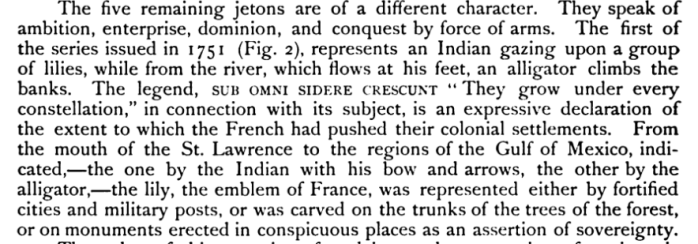

Jeton, Louis XV, Sub Omni Sidere Crescunt, 1751. Collection: The American Numismatic Society.

Today I became aware of a fascinating jeton (a small medal-like token) from the reign of Louis XV. The reverse carries the image of what was thought be a First Nations Person of New France (Canada). This ‘Amerindian’ has plumes in his hair, he carries a bow, and gazes over his shoulder to look at an crop of giant lilies (the fleur de lys of France). The inscription—Sub Omni Sidere Crescunt [under every constellation they grow]—a reference to the lilies of France (her colonies) that grow simultaneously in lands across the globe.

I was excited to find another numismatic image of what I believed to be an indigenous warrior from New France. The only other numismatic representation of that kind is found on the Honos et Virtus [honour and virtue] medal awarded to Amerindian warriors who collaborated with the French colonists.

That medal depicts the First Nations warrior in classical garb, wearing the toga of an ancient Roman, and in a comparative state of undress compared to the centurion-like figure (the representative of France) with whom he shakes hands.

In comparison, the figure from the jeton is dressed in what appears to be traditional costume. It is, nevertheless, a rather generic and fictionalised version of what an indigenous person from the New World ought to look like.

The exergue beneath the feet of our warrior bears the words Col. Franc. De LAM. 1751. Numismatists, have assumed that this text is a contraction of ‘Le colonies françaises de l’Amerique’ [French colonies in America]. This is the meaning given by Charles Wyllys Betts, whose catalogue American Colonial History Illustrated by Contemporary Medals (1894) is the standard text for citations of medals that relate to the history of North America and Canada:

Betts took his reading, it seems, from a notice published in the American Numismatic Journal in 1879:

George Parsons wrote a longer article for the American Numismatic Journal on the ‘Colonial Jetons of Louis XV’ in 1884. He makes the following interpretation of the jeton in question:

That jeton, with its wonderfully evocative image of a native in the colonies gazing upon the lilies of France, is indeed ripe for such an interpretation. In the copy of the jeton described by Parsons there’s even an alligator climbing from the water – presumably a reference to the native fauna found in the southern parts of the French territories in the New World.

Sadly, it seems that these worthy American numismatists of the nineteenth century had not found any contemporary French descriptions of that jeton. Had they done so, they would have learnt that it was, in fact, intended to celebrate the French colony in Martinique, as a description from the Mercure Galant of April 1751 confirms.

In an article title ‘Devises pour les jettons du premier de janvier 1751’ [Devises for the jetons of the first of january 1751], our jeton is described as:

“Une Sauvage, & des Lys plantés auprès de lui. Légende: Sub omni sidere crescunt; ils croissent dans tous les climats. Exergue, Colonies Françoises de la Martinique, 1751.”

[A savage, & some lilies planted next to him. Legend: sub omni sidere crescunt; they grow in every climate. Exergue, French colonies of Martinique, 1751.]

So it seems that this image of a First Nations warrior from Canada was intended to be an indigenous man of Martinique. There is something to be said here about the generic way in which native people of colonised territories were depicted in the ancien-régime. It is true that this image of a ‘noble savage’ among the lilies could just as easily have represented any number of the many peoples whose lands were occupied by Europeans in the early modern period.

This is an example of the kinds of misconceptions that have been passed down from nineteenth-century descriptions of coins, medals, and jetons that have been take up uncritically by the dealers and collectors of American numismatics who have sought them out. To be sure, a connection with the colonial history of America and Canada has made this jeton highly collectible in those countries. Where an average Louis XV jeton might be sold for US$50-100, copies of this piece have sold for over US$1,000.

Contracted inscriptions can lead to confusion and lasting misconceptions. This was the very opposite of what the designers of medals and jetons had intended. These miniature monuments carried inscriptions that were supposed to preserve historical information for posterity – to provide clarity about historical details that might otherwise be lost.

For me, this is a timely reminder to return to the archive, and to render my own readings of artefacts from the ancien-régime, rather than relying on what has come before.

Robert Wellington.

8 February 2018.